What happens when a routine sore on the foot refuses to heal and quietly becomes a major problem? A non-healing foot ulcer is not simply a slow wound; it's a signal that underlying biology or circulation has gone off course. Left unchecked, these ulcers can lead to infection, hospital admission, and, in severe cases, amputation. This blog explains why ulcers fail to heal, how clinicians assess them, and which treatment options, both basic and advanced, offer the best chance of recovery.

Synopsis

Why Do Some Foot Ulcers Refuse To Heal?

A wound heals when the local environment, blood supply, and infection control are favourable. When any one of those pillars is missing, wounds stall in the inflammatory phase and become chronic. Two of the most important drivers behind chronic foot wounds are peripheral neuropathy and peripheral arterial disease.

Peripheral neuropathy reduces pain sensation, so people with nerve damage may not notice injuries early and continue to put pressure on the same spot. Peripheral arterial disease restricts blood flow, starving tissue of oxygen and nutrients essential for repair. When neuropathy and poor blood supply coexist, as is common in people with diabetes, a small blister or thorn can progress to a deep, slow-healing ulcer.

Other contributors include:

-

Prolonged pressure (especially on the plantar surface)

-

Infection and biofilm formation

-

Poor glycaemic control

-

Repeated trauma

-

Certain medications

Systemic factors, such as malnutrition, renal disease, and immunosuppression, also reduce healing capacity. Doctors use these observations to target investigation and treatment rather than treating the wound in isolation.

Common Causes And Typical Features

|

Causes |

Why It Prevents Healing |

What Clinicians Look For |

|

Peripheral neuropathy |

Repetitive unrecognised trauma; altered pressure distribution |

Loss of protective sensation on monofilament testing; callus formation |

|

Peripheral arterial disease |

Poor blood supply; low oxygen tension prevents repair |

Weak/absent pulses, low ankle-brachial index, slow capillary refill |

|

Infection / Biofilm |

Bacterial burden and biofilm block healing processes |

Increasing pain, purulence, odour, and raised inflammatory markers |

|

Pressure / Mechanical stress |

Ongoing pressure prevents granulation tissue formation |

Ulcer over pressure points, abnormal gait, inappropriate footwear |

|

Systemic factors |

Poor glucose control, malnutrition, and renal failure impair repair |

High HbA1c, low albumin, other organ dysfunction |

Principles of Management: The “What Works” Framework

Successful management follows a clear sequence: treat infection, remove devitalised tissue, restore blood supply if required, relieve pressure, optimise systemic factors, and choose appropriate dressings and advanced therapies when needed. This sequence is embedded in modern guidelines and repeatedly supported by clinical literature.

|

Treatment |

When To Use |

Evidence/Notes |

|

Sharp debridement |

Any wound with necrotic tissue or slough |

Standard of care: improves the wound bed for healing. |

|

Appropriate systemic antibiotics |

Clinical infection, spreading cellulitis, osteomyelitis |

Based on tissue culture, avoid routine antibiotics for colonised wounds. |

|

Offloading devices |

Plantar weight-bearing ulcers |

Highly effective; a total contact cast is the gold standard when feasible. |

|

Revascularisation |

Significant PAD/ischaemia |

Referral to the vascular service improves limb salvage and healing. |

|

Advanced dressings (foam, alginate, antimicrobial) |

Manage exudate, protect wound |

Chosen by wound characteristics, no one dressing heals all ulcers. |

|

Negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) |

Large, exuding wounds post-debridement |

Useful adjunct in selected cases to promote granulation. |

|

Hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) |

Selected ischaemic or refractory ulcers as an adjunct |

Evidence is mixed; it may reduce amputation rates in select patients, but it is not a routine first-line. |

|

Skin substitutes/growth factors |

Non-healing despite the best standard care |

Considered as adjuncts per the specialist wound service and guideline criteria. |

Practical Steps Patients And Caregivers Can Take

After explaining the clinical pathway, here are simple, practical actions families can adopt immediately:

-

Inspect feet daily for new sores or blisters.

-

Keep blood sugar and other chronic conditions under control.

-

Wear appropriate protective footwear and avoid walking barefoot.

-

Seek early medical review for any foot wound that is not shrinking after two weeks.

-

Keep an up-to-date medication list and communicate changes to the wound care team.

-

Attend appointments for vascular or podiatry assessment without delay.

These behaviours help identify problems early, when interventions are simpler and success rates higher.

Conclusion

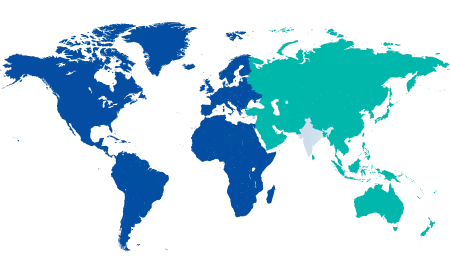

A non-healing foot ulcer is a clinical red flag that demands a systematic response: identify and treat infection, remove necrotic tissue, ensure adequate blood supply, relieve pressure, and optimise the patient’s overall health. When first-line measures fail, evidence-based adjuncts, carefully chosen and delivered by multidisciplinary teams at Manipal Hospitals, can offer additional hope. Prompt assessment and coordinated care are the best ways to reduce complications and preserve limbs.

If you or a loved one has a foot ulcer that is not healing, early consultation with a vascular or wound care specialist is crucial. Book an appointment with an experienced specialist at Manipal Hospitals Old Airport Road to ensure timely diagnosis, advanced treatment, and the best chance of limb preservation.

FAQ's

If an ulcer shows little or no improvement after two to four weeks of best standard care (appropriate debridement, offloading, and infection control), clinicians usually consider investigating further and escalating treatment.

No. Antibiotics are indicated for clinical infection. For colonised but uninfected wounds, systemic antibiotics do not promote healing and can cause harm; targeted therapy based on tissue cultures is preferred for true infections.

Yes. Poor glycaemic control impairs multiple aspects of wound healing and increases infection risk. Optimising blood sugar is a core part of chronic wound care.

If pulses are weak or absent, ankle-brachial index is low, or the ulcer looks ischaemic (pale, painful, and slow to heal), an urgent vascular assessment and consideration of revascularisation are warranted.

HBOT can be helpful in selected, refractory, or ischemic ulcers but is not a routine first-line therapy. Evidence supports the benefit for some patients but is mixed overall; it should be considered by specialist teams after standard measures have been applied.

7 Min Read

7 Min Read

-_A_Life-Changing_Advance_in_Treating_Movement_and_Neurological_Disorders.png)