_Causes_Risks_and_Treatment.png)

The most common question regarding liver health: Is fatty liver always caused by drinking alcohol, or are there other reasons?

Yes, fatty liver is increasingly common today, but it’s not just about alcohol. In fact, most people diagnosed with fatty liver on an ultrasound don’t drink heavily; instead, the problem is closely linked to metabolic health.

The term formerly used, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), has been updated to metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) to reflect this connection. If you’ve been told your liver shows “fatty change”, it’s important to know what that really means, what increases your risk, and the practical steps you can take to protect your liver and your long-term health.

In this blog a liver specialist and liver transplant specialist discusses everything you need to know about fatty liver, including what is MASLD, its causes, symptoms of fatty liver, treatment, and management strategies.

Synopsis

- What Exactly is MASLD?

- Who is at Risk? The 5 Metabolic Markers to Watch for

- Why You Should Take Fatty Liver Seriously?

- How is Fatty Liver Disease Diagnosed and Assessed?

- The Single Most Effective Approach: Lifestyle First

- Medical Treatments and When to Consider Them

- Liver Screening: Who Should Be Assessed and How Often?

- Practical Steps You Can Start Today

- When to See a Hepatologist?

- Conclusion

What Exactly is MASLD?

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease or MASLD in simple terms is defined as excess fat stored in liver cells that is not caused by significant alcohol consumption. The key difference with the older term is the emphasis on metabolic dysfunction. This implies fatty liver is not just related to alcohol consumption, but, it is a part of a broader metabolic profile that usually includes issues such as insulin resistance, high blood sugars, abnormal lipids, high blood pressure, or excess abdominal fat. The new nomenclature aims to make clear that fatty liver is frequently a metabolic disease and should be managed as part of overall cardiometabolic health.

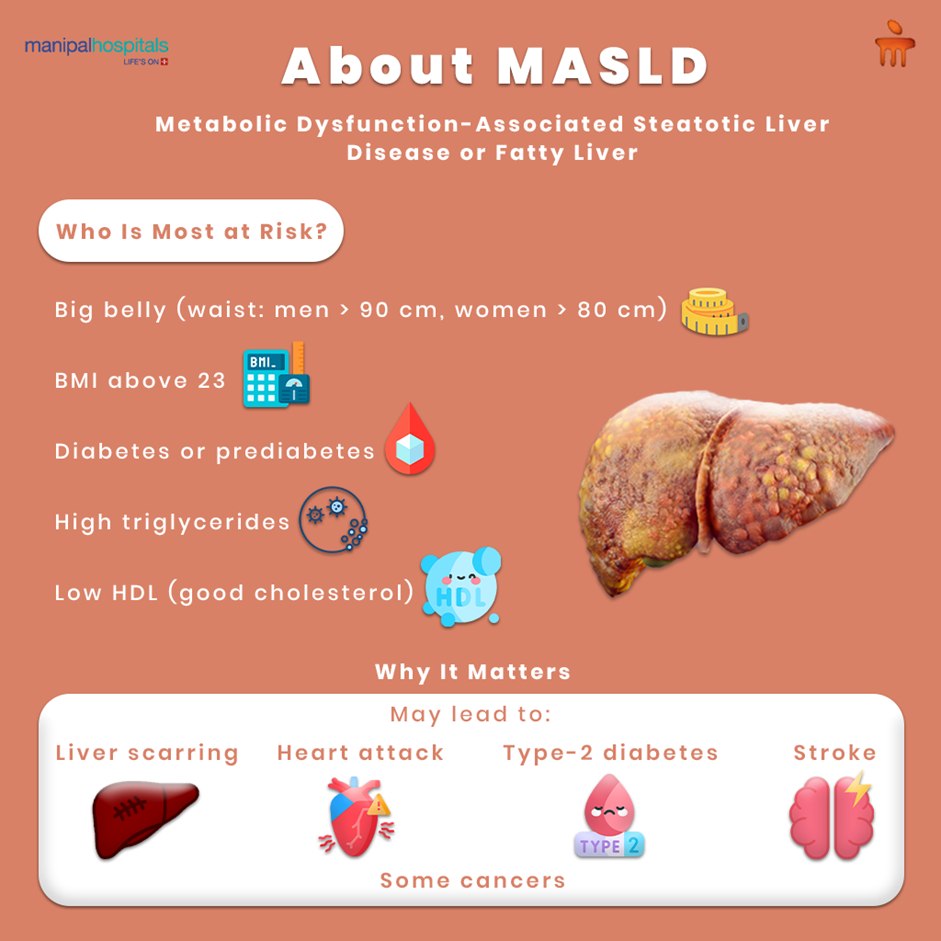

Who is at Risk? The 5 Metabolic Markers to Watch for

In practice, a diagnosis of MASLD is likely if a person has liver steatosis on imaging and at least one cardiometabolic risk factor. Common, measurable markers of metabolic dysfunction include:

-

Raised body mass index (BMI), in South Asian populations, a BMI above about 23 is already concerning

-

Increased waist circumference (>90 cm in men, >80 cm in women in many studies)

-

Diabetes or prediabetes

-

High triglycerides (for example >150 mg/dl)

-

Low HDL (“good”) cholesterol (men: less than 40 mg/dl, women: less than 50 mg/dl)

If you have any one of these, your metabolic risk is higher, and so is the likelihood that fatty liver may be present or progress. These cut-offs and their relevance in South Asian populations are supported by regional studies and international guidance.

Why You Should Take Fatty Liver Seriously?

Fatty liver is not just a benign scan finding. In many people, it remains simple steatosis, but for some it progresses to steatohepatitis, a form of inflammation in the liver, which can then cause scarring (fibrosis). Fibrosis, if it advances, leads to cirrhosis and raises the small but real risk of liver failure and liver cancer. Beyond the liver, MASLD also signals a higher risk of heart disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes, and some cancers. Often, there are no symptoms in the early stages, which is why incidental findings on blood tests or imaging are so common. Early detection and action change that trajectory.

How is Fatty Liver Disease Diagnosed and Assessed?

A typical pathway looks like this:

-

Initial detection: many cases are first seen as “fatty liver” on ultrasound or as mild abnormalities in liver blood tests (ALT/AST).

-

Risk stratification: clinicians use clinical history (metabolic risk factors), blood tests and simple scoring systems to estimate the risk of advanced fibrosis.

-

Non-invasive tests: Elastography (FibroScan) and blood-based fibrosis markers help assess whether there’s significant scarring without needing a biopsy. These non-invasive tools are now central to practice because they allow safe, repeatable monitoring. If non-invasive tests suggest advanced fibrosis, specialist referral and sometimes a liver biopsy are considered.

The Single Most Effective Approach: Lifestyle First

The cornerstone of treatment for MASLD is lifestyle change. This is where you have the greatest control and where measurable improvements are common.

-

Aim for a calorie deficit so you lose weight gradually. Even modest weight loss (for example, losing around 5–10% of body weight) reduces liver fat and inflammation; greater loss produces larger benefits.

-

Eat with fibre and protein in mind. A pattern such as the Mediterranean diet, rich in vegetables, whole grains, pulses, fish (if you eat it), nuts and olive oil, reduces liver fat even beyond weight loss alone. Ensure adequate protein intake; a commonly recommended target is approximately 1 gram of protein per kg body weight per day unless your clinician advises otherwise.

-

Move regularly. Aim for consistent physical activity. Guidance suggests between 150 and 300 minutes of moderate activity per week, which can be met by something like 45 minutes of brisk activity most days. This helps reduce liver fat even when weight loss is small. Both aerobic exercise and resistance training help.

If you combine a sensible calorie deficit, adequate protein and about 45 minutes of regular exercise, many people will reduce liver fat and improve metabolic health, and some will recover completely from early disease.

Medical Treatments and When to Consider Them

For many people, lifestyle changes are sufficient. However, if you have progressive fibrosis, type-2 diabetes, or are unable to lose weight with diet and exercise alone, there are now medical options that a hepatologist may discuss. These include:

-

medicines to treat underlying metabolic disease (for example, optimising control of diabetes, lipids and blood pressure)

-

certain glucose-lowering agents and newer weight-loss medications that have shown promise in reducing liver fat, inflammation, and fibrosis in trials (your specialist will advise if these are appropriate)

-

and in some cases, clinical trials of drugs specifically targeting fibrosis or steatohepatitis.

Crucially, the decision to begin medication or consider referral depends on the degree of fibrosis and overall clinical risk. Non-invasive tools and specialist evaluation determine the right pathway. Recent practice guidance from leading liver societies outlines how to stratify risk and when to escalate care.

Liver Screening: Who Should Be Assessed and How Often?

You should consider screening if you have metabolic risk factors, for example, if you have diabetes, obesity, or abnormal lipids. Screening may start with liver function tests and an ultrasound, but more importantly, with a formal assessment of fibrosis risk using non-invasive scores and elastography where available. The frequency of monitoring depends on your baseline risk: low-risk people may need less frequent follow-up, while those with diabetes or evidence of fibrosis need closer surveillance. Early identification matters because early fibrosis can be stabilised or even improved with the right treatment.

Practical Steps You Can Start Today

A short action plan you can take right away:

-

Review your weight and waist measurement; if your BMI is above 23 or your waist circumference is high, talk to your doctor.

-

Check if you have diabetes or abnormal lipids, if you haven’t had recent tests, ask for them.

-

Aim for a calorie deficit while keeping protein and fibre adequate (target ~1 g protein/kg/day unless advised otherwise);

-

Do around 45 minutes of brisk activity most days, and include resistance work twice weekly;

-

If a scan or blood tests show fatty liver, ask about non-invasive fibrosis assessment (FibroScan or blood tests) to understand your risk.

These are practical, evidence-based steps that reduce liver fat and lower the chance of progression.

When to See a Hepatologist?

Make an appointment with a hepatologist if you have:

-

abnormal liver tests that persist

-

ultrasound showing fatty liver plus diabetes or other metabolic risk factors

-

evidence from non-invasive tests suggesting fibrosis

-

unexplained symptoms such as significant fatigue, jaundice, or signs of advanced liver disease.

A hepatologist will personalise assessment, arrange the right tests and, if needed, discuss medical therapies or clinical trials.

Conclusion

Fatty liver, now commonly called MASLD, is common but manageable. It’s a signal from your body that metabolic health needs attention. The strongest tools you have are a calorie-wise diet, adequate protein and fibre, and regular exercise. If tests show liver fat, don’t dismiss it as a harmless scan finding: discuss fibrosis assessment and a personalised plan with a hepatologist or your doctor. With the right approach, many people reduce liver fat, improve metabolic health and avoid long-term complications.

FAQ's

Diet composition, portion sizes and physical activity matter more than whether you eat meat or drink alcohol. A diet high in simple calories (sugary foods, refined carbohydrates, fried snacks) and low in fibre, plus a sedentary lifestyle, can cause calorie excess, weight gain and accumulation of fat around the belly (visceral adiposity). That visceral fat is strongly linked to MASLD. Even vegetarians can develop MASLD if their overall metabolic health is poor. Addressing portion control, increasing fibre and ensuring adequate protein, plant or animal, helps a great deal.

Yes, especially in the early stages. Weight loss through a calorie deficit reduces liver fat; losing around five to ten per cent of your body weight often yields clear improvements in liver tests and imaging. Exercise improves liver fat independently of weight loss. If fibrosis has started, even it can be reversed when apt lifestyle changes and medical treatment is combined. Hence, early detection is important.

Clinical guidance suggests 150–300 minutes of moderate aerobic activity weekly. Practically, this may look like around 30–60 minutes most days. The 45-minute target mentioned in everyday practice is a sensible, achievable goal for many people. Include resistance training twice a week for additional metabolic benefit.

No. The quality of fat matters more than total elimination. Unsaturated fats (for example, olive oil, nuts, seeds, fatty fish, where appropriate) are part of heart-healthy and liver-friendly diets such as the Mediterranean pattern. Avoid excess refined sugars, sugary drinks and trans fats. Focus on whole foods, fibre and balanced meals rather than demonising all dietary fat.

Varices are enlarged veins in the portal vein or stomach created by high portal pressure from scarring. If they bleed, it can cause massive blood loss. Endoscopic treatment and medicines help prevent bleeding.

Initial tests include liver function bloods, and an ultrasound. To assess fibrosis non-invasively, your clinician may use blood-based scores and elastography (FibroScan). These tools help determine if scarring is present and whether specialist referral or biopsy is needed. They’re safe, repeatable and central to modern care.

7 Min Read

7 Min Read